You could represent possible behaviors as a graph and then search over it to decide which behavior to execute. You could represent players (nodes) and their friendships (edges) in a social game. You could represent rooms (nodes) and hallways (edges) in a dungeon exploration game. Although graph search is an obvious match for pathfinding on maps, you can also use it for lots of other problems. I also didn’t cover graphs for other uses in games. I typically use a list of edges per node, but you could also use a global set of edges, or a matrix representation that keeps track of which pairs of nodes have an edge between them. I didn’t cover alternate representations of edges. I plan to build some demos of non-grid pathfinding graphs too, but grids are easier to explain. They work with graph-based pathfinding algorithms. Why do I keep using grids with my pathfinding tutorials? Because they’re easy to use, and were incredibly common back when I started working on games. In your graph search function, you’ll have to exit before visiting nodes with Infinity as the cost.Īltering the weights may be easier if you want to change the obstacles after the graph is constructed. If obstacles occupy the squares, you can mark edges leading to obstacles as having Infinity as the weight. If obstacles occupy the borders between squares, you can mark those edges with Infinity as the weight. If obstacles occupy the squares, you can remove the edges that lead to those squares. If obstacles occupy the borders between squares, you can remove those edges from the graph by adding an additional check in the neighbors() function. You also need to remove the corresponding edges, which happens automatically if you’re using “ if neighbor in all_nodes” to test whether an edge is added, but not if you’re testing whether x/y are in range. If obstacles occupy grid squares, you can remove those nodes from the graph ( all_nodes). How do we represent a grid’s obstacles in a graph form? There are three general strategies: In a weighted directed graph, we might mark downhill edge B→C with weight 2 and mark uphill edge C→B with weight 5 to make it easier to walk downhill. In a weighted undirected graph, we might mark a paved road as weight 1 and a twisty forest path as weight 4 to make the pathfinder favor the road. A weighted graph allows numeric weights on each edge. One annotation that shows up often in pathfinding algorithms is edge weights. In addition, you can annotate nodes and edges with extra information. Node B could have more than one edge B→C leading to node C. Being able to swim across a river or take a raft across the same river is an example in games.

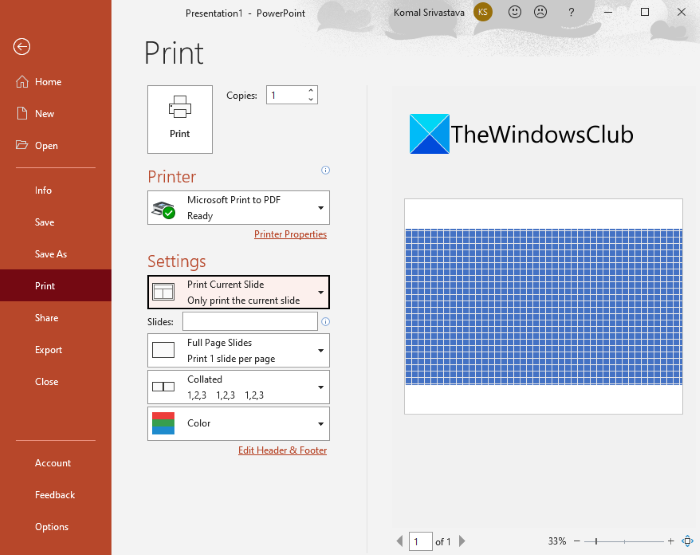

GRAPH GRID MAKER CODE

Here’s code for the 20x10 map we generated earlier: def neighbors( node): This only works if the map is rectangular. Neighbor = + dir, node + dir]Īn alternate way to check is to make sure the coordinates are in range. However, we want to return only the nodes that we can move to, so we’ll add a check: def neighbors( node): If your game allows diagonal movement, you’ll have eight entries in dirs. We call these neighbors: def neighbors( node):ĭirs =, ,, ] For any node we need to know the other nodes connected to this one by an edge.

The edges are going to be the four directions: east, north, west, south. We aren’t limited to rectangles, but for simplicity, here’s the code for a 20x10 rectangle: all_nodes =

When working with a square grid, we need to make a list of nodes.

GRAPH GRID MAKER HOW TO

Let’s see how to encode a grid in graph form. Pathfinding algorithms that can harness the additional properties of a grid can run more quickly than regular A*. Graph search algorithms don’t really “understand” the layout or properties of a grid. You’ll get the same answer for both diagrams.

Try it for yourself: make a list of the nodes in the graph, and then make a list of the edges connected to each node.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)